ISE05/15-16

| Subject: | food safety and environmental hygiene, public health, nutrition-related diseases |

- The Government has implemented a mandatory nutrition labelling scheme for prepackaged foods since 1 July 2010 to help consumers make informed food choices. This labelling scheme requires prepackaged foods to present specified nutrition information, usually in a tabular format on the back or side of packaging. Yet, there are increasing concerns about the legibility of nutrition information displayed on the labels. Members have thus urged the Government to review the food labelling regulations and, if necessary, introduce legislative amendments to ensure the legibility of food labels.1Legend symbol denoting See Legislative Council Secretariat (2014).

- Facing similar concerns about back-of-pack or side nutrition labelling, some overseas places such as the United Kingdom ("UK"), Australia and Singapore have in recent years implemented voluntary front-of-pack ("FOP") nutrition labelling schemes while mandating back-of-pack nutrition declarations.2Legend symbol denoting In Australia, back-of-pack nutrition labelling is mandatory for all prepackaged foods. The UK follows the food labelling regulation of the European Union which provides for mandatory nutrition labelling for most prepackaged foods from December 2016. In Singapore, nutrition labelling is mandatory only for prepackaged foods making nutrition claims or permitted health claims. These FOP labels carry simplified and easy-to-understand information on the key nutritional aspects/characteristics of foods to help consumers make healthier food choices. This issue of Essentials highlights three common approaches of FOP nutrition labelling and the experiences in implementing FOP nutrition labelling in selected places.

Implementation of the nutrition labelling scheme in Hong Kong

- According to the Centre for Food Safety ("CFS"), nutrition is essential for growth, tissue repair and maintenance of good health.3Legend symbol denoting See Centre for Food Safety (2008). Providing nutrition information on food labels is an important public health tool to promote a balanced diet.4Legend symbol denoting According to the Centre for Food Safety (2008), many chronic degenerative diseases such as coronary heart disease, diabetes and certain types of cancer are related to an imbalanced diet. These nutrition-related diseases are important public health problems in many parts of the world including Hong Kong. Under the mandatory nutrition labelling scheme, all prepackaged foods, unless otherwise exempted, are required to label the content of energy and seven specified nutrients (namely protein, carbohydrates, total fat, saturated fat, trans fat, sodium and sugars), and the amounts of any claimed nutrients such as dietary fibre, minerals and vitamins.

- According to a survey commissioned by the Audit Commission in 20115Legend symbol denoting See Audit Commission (2011)., factors such as poor legibility of the nutrition labels6Legend symbol denoting The Audit Commission also conducted market surveys between May and August 2011 which found that the nutrition labels of some prepackaged foods were too small in font size, and the text and background of some were not shown in distinct contrast, thus making the nutrition information very difficult to read. CFS subsequently issued the Trade Guidelines on Preparation of Legible Food Label in May 2012 with a view to improving the legibility issue of nutrition labels. However, a study conducted by CFS and the Consumer Council in 2013 on the legibility of nutrition labels of prepackaged foods of relatively small package size revealed that 63 out of 100 sampled products did not follow the recommendations of the Guidelines and had legibility issues. and inadequate understanding of the information provided had hindered the general public from reading the nutrition labels. Similarly, a survey commissioned by CFS in 20127Legend symbol denoting See Consumer Search Hong Kong Ltd (2012). recommended enhancing public understanding of the terminology used in the nutrition labels in order to improve general knowledge on nutrition labels.

Front-of-pack nutrition labelling approaches

- Some overseas places have implemented voluntary FOP labelling schemes recently aiming at (a) helping consumers make informed food choices by providing them with simple and easy-to-understand information that indicates the relative nutritional quality of a food product either within or between product categories; and (b) encouraging food manufacturers to develop healthier products by reformulation of existing products or development of new ones in order to meet the criteria of carrying a favourable nutrition label. Broadly speaking, there are three such labelling approaches, namely the "Guideline daily amounts" ("GDA") labelling approach which emphasizes how a food product fits in a consumer's overall diet, and the "colour-coded" and the "summary indicator" labelling approaches which aim at highlighting the nutritional quality of a food product based on specific nutritional criteria.8Legend symbol denoting There is no standardized approach for presenting nutrition information among the various FOP nutrition labelling schemes. For example, the Guidelines on Nutrition Labelling adopted by the Codex Alimentarius Commission do not include any direction for FOP labelling. The Codex Alimentarius Commission was established by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the World Health Organization in 1963 to develop harmonized international food standards, guidelines and related codes of practice.

"Guideline daily amounts" labelling approach

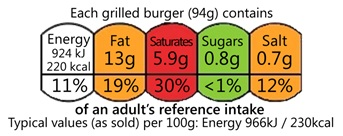

- GDA means the amounts of energy and nutrients recommended by food experts for an average healthy person to have a balanced diet. The GDA labelling approach aims at enabling consumers to quickly and easily determine the nutritional profile of a food product against the average daily requirements of a healthy person by presenting the amounts of energy and key nutrients contained in one serving or portion of the product as a percentage of GDA (Figure 1). Nevertheless, the GDA labels only serve as a guide for consumers, as an individual's nutritional requirements can vary with gender, weight, activity levels and age.

Figure 1 - Example of "Guideline daily amounts" labelling approach

Source: Food Standards Agency (2010). - The GDA labelling approach has been commonly adopted by food manufacturers and retailers in the European Union ("EU") under their own initiatives to provide consumers with simplified nutrition information and to enhance the competitive advantage of their brands. The new Regulation on the Provision of Food Information to Consumers9Legend symbol denoting The new Regulation provides for mandatory nutrition labelling for most prepackaged foods and the related provisions will take effect in December 2016. Meanwhile, nutrition labelling in the EU is only mandatory for products making nutrition or health claims. adopted by the EU in 2011 sets out the rules governing the content and presentation of voluntary FOP labelling based on the GDA approach. While the Regulation adopts the term "reference intakes" instead of "GDA", the basic principle underlying the two terms is the same. The Regulation further stipulates that reference intakes must have calories listed alone or with the four most important nutrients, i.e. fat, saturates, sugars and salt, that may increase the risk of developing diet-related diseases.

Colour-coded labelling approach

- The colour-coded labelling approach aims at helping consumers see at a glance the levels of key nutrients of foods sold through retail outlets and make healthier food choices. A typical example of such approach is the traffic light labelling scheme introduced in the UK in the mid-2000s by the Food Standards Agency ("FSA"), the government regulator for food safety and food hygiene across the country. Under the scheme, a food product's levels of fat, saturated fat, salt and sugars are colour-coded on the FOP label with red for high level, amber for medium level and green for low level (Figure 2). The classification is based on threshold criteria set by FSA applicable across various product categories.

Figure 2 - Example of traffic light labelling scheme

Source: Food Standards Agency (2010). - Since its introduction, the traffic light labelling scheme has been well received by consumers in the UK as it enables easy comparison of the nutritional quality of foods across and within product categories. However, some food manufacturers and retailers in the UK consider the traffic light labelling scheme too simplistic. In particular, the "red" code may imply "danger", leading some consumers to stop taking certain red-coded food products. As a result, some manufacturers have insisted on using the GDA labelling system that was originally devised in the UK in 1998.

- In 2010, voluntary provision of FOP labelling was widespread in the UK with around 30 000 products (around 80%) of processed foods carrying some form of FOP labelling such as GDA or traffic light labelling.10Legend symbol denoting See Food Standards Agency et al. (2012). The results of a consultation exercise on FOP nutrition labelling conducted by the UK government in 2012 reflected that stakeholders, including the food industry, supported the government to drive greater consistency in the provision of FOP nutrition information in order to reduce consumer confusion and enhance effectiveness of FOP nutrition labelling.11Legend symbol denoting See Food Standards Agency et al. (2013). Subsequently, the UK government introduced a standardized labelling scheme in 2013 which combined traffic light coding with GDA nutrient percentages on FOP labels (Figure 3).

Figure 3 - Example of standardized labelling scheme

Source: Department of Health et al. (2013).

Summary indicator labelling approach

- The summary indicator labelling approach refers to the use of a single symbol, icon or score to provide summary information about the nutrient content of a product. Summary indicator labels are considered to be easy to understand and can facilitate easy comparison of nutritional quality of foods within product categories. Notable examples are the Healthier Choice Symbol ("HCS") programme implemented in Singapore and the Health Star Rating ("HSR") system in Australia.

- The Singapore government implemented the HCS programme in 1998. Products carrying HCS are generally lower in total fat, saturated fat, sodium, or sugars; or higher in dietary fibre or calcium as compared with similar products within the same food category (Figure 4). Separate sets of nutritional criteria are used for evaluating different product categories. As at August 2015, about 325 food companies had participated in the scheme, covering about 3 000 products.12Legend symbol denoting See Singapore Health Promotion Board (2015a).

Figure 4 - Examples of Healthier Choice Symbol

Source: Singapore Health Promotion Board (2015b). - The HCS programme has received positive support from consumers and the trade. According to the study commissioned by the Health Promotion Board13Legend symbol denoting In Singapore, the Health Promotion Board is a governmental organization assuming the role of the main driver for national health promotion and disease prevention programmes in the country. in 2008, about 80% of Singaporeans had used HCS when shopping. The availability of products with HCS increased from 300 in 2001 to about 3 000 in 2015. In specific product categories such as liquid milk, sweetened drinks and juices, the percentage of sales of HCS products compared to sales of total number of products (including both HCS and non-HCS products) in the same category increased from 30% in 2001 to 54% in 2010.14Legend symbol denoting See Singapore Health Promotion Board (2013 and 2015a).

- In Australia, the Commonwealth government introduced the HSR system in 2014.15Legend symbol denoting The leading food trade association in Australia introduced a GDA labelling scheme namely the Daily Intake Guide scheme under its own initiative in 2006 and about 7 200 products have adopted the scheme since then. However, there were views that the scheme required a higher level of literacy and numeracy to interpret and might not provide nutrition guidance to those who might need it most. Under the system, similar packaged foods are scored and assigned a rating ranging from half a star to five stars based on nutrition information such as energy, risk nutrients (e.g. saturated fat, sodium and sugars), and positive nutrients (e.g. dietary fibre and protein) (Figure 5). The higher number of stars suggests higher level of healthfulness. The FOP label can display the star rating with or without additional specific nutrient content of the product.

Figure 5 - Example of Health Star Rating system

Source: Commonwealth of Australia (2015). - According to a consultancy study commissioned by the Department of Health of the Commonwealth government, the costs of implementing the HSR system were estimated to be AUS$60 million (HK$332 million) over a five-year period assuming that the system was adopted by 9% to 18% of products. Of the total costs, 67.5% was borne by food businesses, 22.5% by the government and 10% by non-governmental organizations.16Legend symbol denoting See PricewaterhouseCoopers (2014b). Another study commissioned by the Department estimated that the costs of major labelling change to food businesses as a result of regulatory or non-regulatory changes might range from about AUS$5,200 (HK$28,800) to AUS$12,300 (HK$68,100) per product depending on the types of packaging.17Legend symbol denoting See PricewaterhouseCoopers (2014a).

- An assessment of the impact of the HSR system on small businesses in Victoria indicated that some small businesses would welcome the HSR system if their food products could achieve high star ratings. In such cases, the HSR system could be seen as an official validation of existing product branding and might open up new markets amongst consumers who would not usually be guided by nutritional content. However, many small businesses had reservations about the relatively high costs of implementing the system and the risks to their brand value if their products could only obtain low star ratings.18Legend symbol denoting See The Centre for International Economics (2014).

Observations

- Conventional back-of-pack or side nutrition labelling in the format of nutrition facts table has its own limitations as it may not be easy for consumers to read and understand the information on the labels. The aim of this labelling approach is to provide information in sufficient detail to allow consumers to choose nutritious foods, or to verify a nutrition claim made on the label. Yet, many consumers may find it difficult to interpret a large amount of information on a nutrition facts table. The development of voluntary and graphical FOP nutrition labelling, to supplement conventional back-of-pack or side labelling schemes, represents an effort to provide consumers with simple, easy-to-understand and interpretive nutrition information. Graphical FOP nutrition labelling favours the inclusion of fewer nutrients, and focuses on clearer interpretation of basic nutrients. It thus represents an important shift from the provision of nutrition information to the understanding of nutrition information to assist consumers in making healthier food choices.

- That said, there is at present no consensus model for presenting nutrition information on FOP labels. Evidence on the impact of the various schemes on purchasing behaviour, and therefore on their relative effectiveness in helping consumers make healthier choices, also remains limited. Hence, while it is noticeable that there is an increasing trend of the use of graphical FOP labelling in prepackaged foods, the FOP labelling schemes are at the moment provided voluntarily by food businesses in selected places. Nevertheless, all the three selected places, i.e. the UK, Singapore and Australia have taken the lead in developing a standardized FOP labelling approach for the trade to follow and promoting the awareness and usage of the label among the public in order to enhance the impact of the respective FOP labelling schemes.

Prepared by Ivy CHENG

Research Office

Information Services Division

Legislative Council Secretariat

9 December 2015

Endnotes:

References:

| Hong Kong

| |

| 1. | Audit Commission. (2011) Report No. 57 of the Director of Audit - Chapter 3: Food Labelling.

|

| 2. | Centre for Food Safety. (2008) Technical Guidance Notes on Nutrition Labelling and Nutrition Claims.

|

| 3. | Centre for Food Safety. (2014) Legibility of Nutrition Labels in Prepackaged Food in Hong Kong - Abstract.

|

| 4. | Centre for Food Safety. (2015) Nutrition Information on Food Labels.

|

| 5. | Consumer Search Hong Kong Ltd. (2012) Survey on Public Knowledge, Attitude and Practice regarding Nutrition Labelling 2012 - Summary.

|

| 6. | Food and Health Bureau et al. (2014) Implementation of the Nutrition Labelling Scheme. LC Paper No. CB(2)1461/13-14(03).

|

| 7. | Legislative Council Secretariat. (2014) Report of the Panel on Food Safety and Environmental Hygiene for submission to the Legislative Council. LC Paper No. CB(2)1959/13-14.

|

| 8. | Legislative Council Secretariat. (2015) Implementation of the Nutrition Labelling Scheme. LC Paper No. CB(2)1621/14-15(04).

|

| 9. | Minutes of Meeting of the Panel on Food Safety and Environmental Hygiene of the Legislative Council. LC Paper No. CB(2)21/15-16.

|

| Others

| |

| 10. | BBC News. (2013) Food labelling: Consistent system to be rolled out.

|

| 11. | Commonwealth of Australia. (2015) Health Star Rating System.

|

| 12. | Department of Health et al. (2013) Guide to creating a front of pack (FoP) nutrition label for pre-packed products sold through retail outlets.

|

| 13. | European Food Information Council. (2012) New insights into nutrition labelling in Europe.

|

| 14. | European Food Information Council. (2015) Global Update on Nutrition Labelling.

|

| 15. | Food Standards Agency. (2010) Front of Pack (FOP) Nutrition Labelling.

|

| 16. | Food Standards Agency et al. (2012) Consultation on front of pack nutrition labelling.

|

| 17. | Food Standards Agency et al. (2013) Front of pack Nutrition Labelling: Joint Response to Consultation.

|

| 18. | Foodwatch. (2012) Research supports traffic light colours.

|

| 19. | Hawkes, C. (undated) Government and voluntary policies on nutrition labelling: a global overview.

|

| 20. | House of Commons Library. (2012) Food Labelling Nutrition - Voluntary Schemes.

|

| 21. | Perez, R. & Edge, M. S. (2014) Global Nutrition Labelling: Moving Toward Standardization? Nutrition Today, vol. 49(2), pp. 77-82.

|

| 22. | PricewaterhouseCoopers. (2014a) Cost Schedule for Food Labelling Changes.

|

| 23. | PricewaterhouseCoopers. (2014b) Health Star Rating System - Cost Benefit Analysis.

|

| 24. | Singapore Health Promotion Board. (2013) Use of Front-of-Pack Labelling Scheme in Singapore.

|

| 25. | Singapore Health Promotion Board. (2015a) Healthier Choice Symbol Programme.

|

| 26. | Singapore Health Promotion Board. (2015b) Know the Difference in Goodness.

|

| 27. | The Centre for International Economics. (2014) Impact analysis of the Health Star Rating system for small businesses.

|

| 28. | Van Kleef, E. & Dagevos, H. (2015) The Growing Role of Front-of-Pack Nutrition Profile Labeling: A Consumer Perspective on Key Issues and Controversies. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, vol. 55(3), pp. 291-303. |