ISE06/17-18

| Subject: | health services, disease prevention |

- Seasonal influenza is an acute illness of the respiratory tract caused by influenza viruses. The three main types of influenza virus are named A, B and C. A and B viruses cause seasonal epidemics of disease almost every year, while C causes only mild respiratory symptoms. While seasonal influenza can affect people in any age group, it may cause severe illness or death in high-risk population groups such as children, the elderly and persons with chronic medical conditions. According to the World Health Organization ("WHO"),1Legend symbol denoting See World Health Organization (2018). vaccination is an effective way to prevent disease and complications from influenza infection. As such, it has recommended annual seasonal influenza vaccination for high-risk population groups.

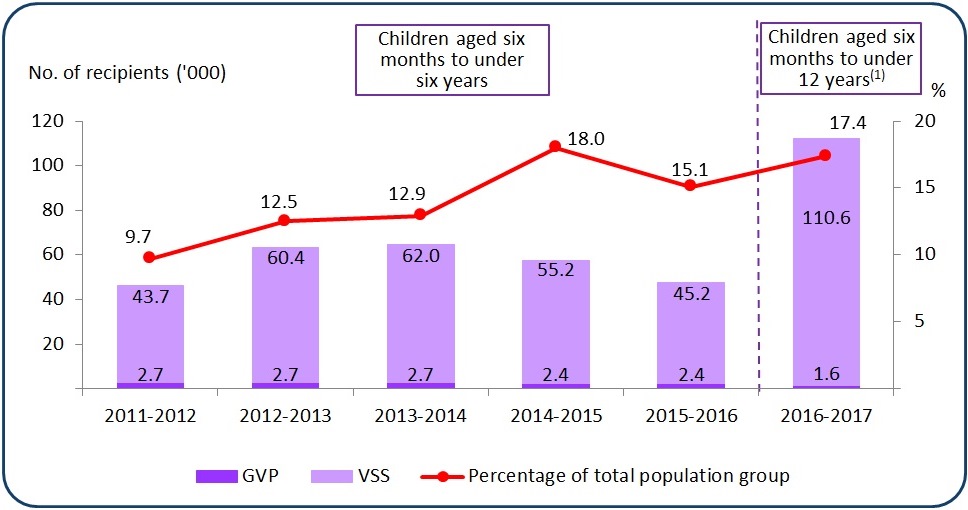

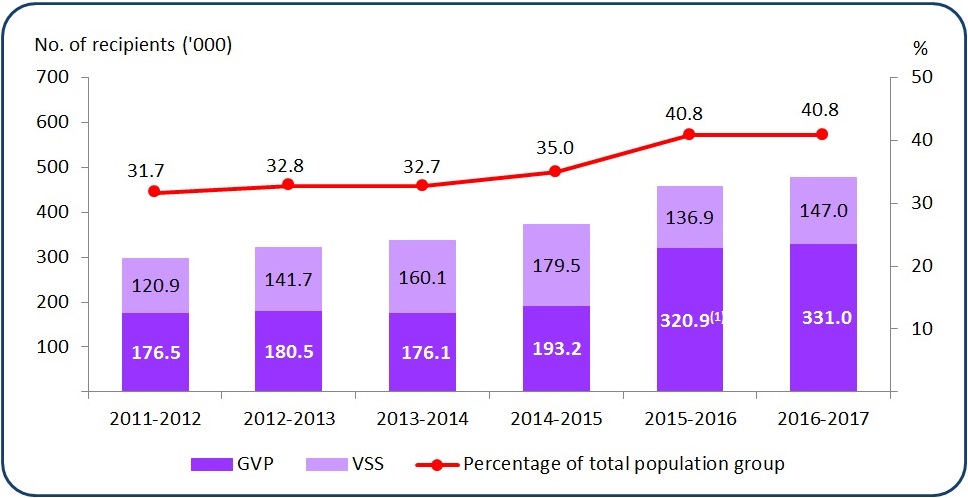

- In Hong Kong, influenza outbreaks are more common every year in the winter (from January to March) and summer (from July to August). The Government has provided free or subsidized seasonal influenza vaccinations to eligible high-risk population groups under its annual vaccination programmes, and about 676 800 persons or 9.2% of the total population had taken vaccinations under those programmes in 2016-2017.2Legend symbol denoting The figure does not include the number of persons receiving vaccination in the private sector at their own expenses. See GovHK (2018a). Specifically, the coverage rates of children aged six months to under 12 years and elderly aged 65 and above were 17.4% and 40.8% respectively in 2016-2017.

- In England of the United Kingdom, the United States ("the US") and Taiwan, the seasonal influenza vaccination programmes run or overseen by their governments3Legend symbol denoting In Hong Kong, England and Taiwan, the governments have run seasonal influenza vaccination programmes targeting at high-risk population groups. In the US, the federal government sets recommendations on the target population for vaccination (i.e. all persons aged six months or above who do not have contraindications to vaccination) and the vaccines to be taken, and monitors the outcomes of vaccinations which are delivered in both the public and private sectors. have achieved much higher coverage rates than that of Hong Kong, ranging from 34.5% to 75.1% for children and 49.2% to 70.5% for elderly aged 65 and above in 2016-2017. This issue of Essentials highlights the issues about the seasonal influenza vaccination programmes in Hong Kong, and the major measures adopted in England, the US and Taiwan for boosting the vaccination coverage rates among target population groups under their seasonal influenza vaccination programmes.

Seasonal influenza vaccination programmes in Hong Kong

- The Government implements the Government Vaccination Programme ("GVP") and the Vaccination Subsidy Scheme ("VSS") annually to provide free or subsidized seasonal influenza vaccination to population groups which are at a higher risk of influenza complications (e.g. children and the elderly). According to the Government,4Legend symbol denoting See GovHK (2018a). past local research studies showed that the effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccination in preventing influenza-associated hospitalization among children ranged from about 40% to 80%. Meanwhile, the study on elderly people living in residential care homes from 2011-2012 to 2016-2017 found that the vaccine effectiveness in preventing influenza-associated intensive care unit admissions or deaths of the elderly ranged from 37% to 69%.

- In 2016-2017, about 430 000 doses of seasonal influenza vaccines were procured by the Government under GVP, costing about HK$23.3 million.5Legend symbol denoting See Food and Health Bureau (2018). Under GVP, free vaccination services are provided to target recipients living in the community through public clinics and those living in residential care homes by visiting medical officers. Community-living recipients include:

(a) persons aged 50 to under 65 years who are recipients of Comprehensive Social Security Assistance ("CSSA") or holders of valid Certificate for Waiver of Medical Charges ("Certificate") issued by the Social Welfare Department; (b) pregnant women who are CSSA recipients or valid Certificate holders; (c) children aged six months to under 12 years from families receiving CSSA or holding valid Certificate; and (d) elderly aged 65 and above. - In 2016-2017, subsidy claimed under VSS amounted to HK$54.8 million.6Legend symbol denoting Ibid. Under VSS, subsidized vaccination services are mainly provided to eligible Hong Kong residents through private medical doctors enrolled in the scheme. Target recipients include: (a) pregnant women; (b) children aged six months to under 12 years; (c) elderly aged 65 years and above; (d) persons with intellectual disability; and (e) persons receiving disability allowance.

- As a percentage of the respective total population groups, the number of children and elders receiving seasonal influenza vaccinations under the Government's GVP or VSS has generally been on the rise in the past few years (Figures 1 and 2). Yet, the rates are still considered relatively low when viewed against the higher risk of influenza complications for children and elders than other age groups. During the recent seasonal influenza outbreak, their influenza-associated admission rates in public hospitals are much higher than those of general population.7Legend symbol denoting During the winter influenza season between January and March 2018, the influenza-associated admission rates in public hospitals for children aged under five years and children aged five to nine years peaked at 8.59 cases and 5.45 cases per 10 000 population respectively. The corresponding rate for the elderly aged 65 and above was 4.25 cases per 10 000 population. These rates were much higher than the peak admission rate for the total population which stood at 1.51 cases per 10 000 population. See Centre for Health Protection (2018a).

- As such, various stakeholders have urged the Government to take measures to boost the vaccination coverage rates, particularly among the high-risk population groups, in an effort to prevent influenza and its complications and reduce influenza-related hospitalization and deaths. Measures proposed include providing outreach vaccination services in schools to extend the coverage of VSS. Recently, the Government has planned to launch a pilot programme in the 2018-2019 school year to provide free outreach influenza vaccination services to participating primary schools, with the objective of increasing the vaccination coverage rate of primary school children. According to the Government, the average participation rate of students in school-initiated outreach vaccination activities was about 50% in the 2016-2017 school year, which was much higher than the overall coverage rate of around 16% for school children aged six to under 12 years.8Legend symbol denoting See Centre for Health Protection (2018b). Yet, only about 10% of primary schools have arranged vaccination activity in schools on their own initiative for students to receive subsidized vaccination.9Legend symbol denoting Barriers to organizing vaccination activity in schools include difficulties encountered by schools in choosing doctors to administer vaccinations and issues relating to maintaining cold chain of the vaccines and handling the clinical waste. See Centre for Health Protection (2018b).

Note: (1) In 2016-2017, the Government extended the scope of GVP and VSS to cover children from the age of "six months to under six years" to the age of "six months to under 12 years".

Figure 2 – Seasonal influenza vaccination coverage rate for elderly aged 65 and above between 2011-2012 and 2016-2017

Note: (1) The figure excludes 98 000 recipients of free 2015 Southern Hemisphere Seasonal Influenza Vaccination under GVP between May to August 2015.

Seasonal influenza vaccination programmes in selected overseas places

- England, Taiwan and the US have promoted the take-up of seasonal influenza vaccination among the high-risk population groups as a major strategy to reduce the morbidity and mortality of seasonal influenza, and to reduce the burden on the healthcare system. These three overseas places have adopted one or more of the following measures to boost the seasonal influenza vaccination coverage rates: (a) delivering vaccinations to school-age children in schools; (b) offering nasal influenza vaccines for children; (c) involving community-based pharmacists in providing vaccination services; and (d) other measures such as recommendations and/or reminders of the medical professionals, and imposing mandatory requirement to take vaccination on specified population groups.

Delivering vaccinations in schools

- England and Taiwan have offered free seasonal influenza vaccination to target children population groups through school-based vaccination services delivered by public or government-commissioned healthcare teams comprising doctors, nurses and/or other support workers.

- England started the children seasonal influenza vaccination programme in 2013-2014 covering children aged 2-3. The government has aimed at gradually extending the scope of the programme to cover older age cohorts up to 16 years old. In the 2017-2018 influenza season, free seasonal influenza vaccination was provided to all children aged 2-9. Among them, children aged two to under four were vaccinated in general practitioners' clinics and aged 4-9 received their vaccination in schools. In 2016-2017, the take-up rate for school-based vaccination programme was 54.9%, higher than that of 34.5% for vaccinations at general practitioners' clinics.10Legend symbol denoting See Gov.UK (2018)., 11Legend symbol denoting 11. The children influenza vaccination programme for 2016-2017 was delivered as follows: two to under five year-olds were vaccinated in general practitioners' clinics and five to under eight year-olds were vaccinated in schools.

- In Taiwan, children aged six months to under six are offered subsidized seasonal influenza vaccination at public or contracted clinics under the seasonal influenza vaccination programme. School-based vaccination programme was first introduced in 200712Legend symbol denoting In 2007, the school-based seasonal influenza vaccination programme in Taiwan only covered primary one and two students. The coverage of the programme has been gradually expanded and it has covered all primary, secondary and vocational school students aged below 18 from 2016. and currently, children/teenagers aged 6-18 are provided with free vaccination in schools. The school-based vaccination programme has helped boost vaccination take-up rate among the target school-age children since its implementation in 2007. In 2016, 75.1% of students aged 6-18 were vaccinated, higher than the vaccination take-up rate of 47.9% for children aged six months to under six.13Legend symbol denoting See衛生福利部疾病管制署(2018年).

Adopting nasal influenza vaccine for children

- England and the US have introduced nasal influenza vaccine to reduce children's resistance to injected seasonal influenza vaccination, in an effort to increase the vaccination take-up rate. The nasal influenza vaccine is sprayed into the nostrils and is easy and painless to take. Unlike the injectable influenza vaccine, nasal influenza vaccine is made from live virus that has been weakened and cannot cause influenza. It is not recommended for use among certain population groups such as children aged under two and children with long-term health conditions.

- England has adopted the nasal influenza vaccine for children since it started the seasonal influenza vaccination programme for children in 2013-2014.14Legend symbol denoting In England, the nasal influenza vaccine was introduced together with the rollout of the children seasonal influenza vaccination programme in the 2013-2014 influenza season. As such, data comparing the take-up rate of nasal influenza vaccine against that of injectable influenza vaccine among children is not available. In 2017-2018, nasal influenza vaccine is provided to children aged two or above, except for those who are severely asthmatic or immunocompromised. According to Public Health England, the nasal influenza vaccine reduced the risk of vaccinated children getting influenza by 65.8% in the 2016-2017 influenza season.15Legend symbol denoting See Gov.UK (2017).

- In the US, the nasal influenza vaccine has been approved for use since 2003 and is recommended for use among healthy non-pregnant and non-immunocompromised persons aged 2-49. While several initial research studies indicated that nasal influenza vaccine was more effective than the injectable vaccine among young children, some recent studies found that it was less effective in preventing the H1N1 strain of influenza. As a result, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ("CDC") had dropped the nasal influenza vaccine from the list of recommended vaccines in the 2016-2017 and 2017-2018 influenza seasons.16Legend symbol denoting See Penn State College of Medicine News (2017). This decision might have contributed to a slight drop in vaccination coverage rate of children aged 5-12 from 61.8% in the 2015-2016 influenza season to 59.9% in the 2016-2017 influenza season.17Legend symbol denoting See Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the United States (2017c). Recently, CDC's Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices has voted in favour of restoring a newly reformulated nasal influenza vaccine as an option for doctors to use during the 2018-2019 influenza season.

Involving community-based pharmacists in providing vaccination services

- In order to boost the seasonal influenza vaccination coverage rate, England and the US have engaged community-based pharmacists as an additional provider of vaccination services. For some people, community pharmacies provide a convenient, accessible and flexible alternative to general practitioners' clinics and other healthcare settings for taking vaccination. In particular, they operate on longer working hours and do not require appointment to be made.

- In England, the National Health Service ("NHS") has since the 2013-2014 influenza season commissioned community pharmacies to provide vaccination services under the seasonal influenza vaccination programme. Pharmacists delivering vaccinations are required to receive appropriate training and attend face-to-face training for both injection technique and basic life support every two years. In 2016-2017, about 8 450 or 71% of community pharmacies in England were commissioned by NHS for providing vaccinations and around 951 000 vaccinations were administered as a result.18Legend symbol denoting See Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee (2018). In that year, around 7% of the vaccinations taken by persons aged 65 and above, and 6% of those aged six months to under 65 years with a medical condition were delivered in community pharmacies.19Legend symbol denoting See Gov.UK (2018).

- In the US, delivery of vaccination, including seasonal influenza vaccination, through community pharmacies has been common in the past two decades with increased take-up rates. Pharmacists delivering vaccinations are required to take part in a certificate training programme recognized by CDC. Meanwhile, over 280 000 trained pharmacists can administer vaccinations in the US. Between 2004-2005 and 2015-2016, the percentage of adults taking seasonal influenza vaccinations in community pharmacies increased from 6% to 25%.20Legend symbol denoting See International Pharmaceutical Federation (2016).

Other measures

- Research studies in the US and England have indicated that recommendation, or invitation/reminder initiated by a healthcare professional is effective in boosting the take-up rate of seasonal influenza vaccination among the target population groups.21Legend symbol denoting See National Foundation for Infectious Diseases (2012) and Dexter, L. J. et al. (undated). In order to enhance the coverage rate of seasonal influenza vaccination, CDC of the US advises healthcare providers to ensure that every person aged six months and above receives a recommendation to get vaccinated and an offer of vaccination, and remind patients to take vaccination with the aid of immunization information systems.22Legend symbol denoting Immunization information systems ("IIS") are confidential, population-based, computerized databases that record all immunization doses administered by participating providers to persons residing within a given area. IIS help doctors determine when immunizations are due and help ensure that their patients get the vaccinations they need. Similarly, NHS in England has required general practitioners to proactively invite or remind eligible patients to take vaccination under the seasonal influenza vaccination programme.

- Since the late 2000s, a few jurisdictions in the US such as New Jersey and Connecticut have imposed mandatory requirement on children aged 6-59 months attending preschools, child care centres or day care centres to take seasonal influenza vaccination in order to reduce transmission in the specified settings as well as in the community. Implementation of the measure has resulted in a high influenza vaccination coverage rate of children aged six months to 4 years in the two states, both standing at about 85% against the national average of 70% in 2016-2017.23Legend symbol denoting See Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the United States (2017b). Nonetheless, the two states have promoted understanding of the mandatory requirement through communication efforts, as well as allowing exemption based on religious ground to manage parents' resistance to the initiative.

Concluding remarks

- As shown in Figure 3, the three overseas places studied have been successful in boosting the seasonal influenza vaccination coverage rates of target population groups by delivering vaccinations in non-conventional settings such as in schools and community pharmacies.

| Total population | Children | Elderly aged 65 and above | |

| Hong Kong | 9.2% | 17.4%

(aged six months to under 12 years) | 40.8% |

| Taiwan(2) | 25.0% | 47.9%

(aged six months to under six years) 75.1% (aged six to 18 years) | 49.2%(3) |

| England(4) | Not available. | 34.5%

(aged two to under five years) 54.9% (aged five to under eight years) | 70.5% |

| The United States(5) | 46.8%

(aged six months and above) | 70.0%

(aged six months to four years) | 65.3% |

| Notes: | (1) | In Hong Kong, Taiwan and England, the figures refer to coverage rates of the respective population groups under the seasonal influenza vaccination programmes implemented by the respective governments. The figures do not cover people who receive vaccination in the private sector at their own expenses. |

| (2) | In Taiwan, the vaccination programme for 2016-2017 was delivered as follows: children aged six months to under six years received their vaccination in public or contracted clinics while children/teenagers aged six to 18 years received their vaccination in schools. | |

| (3) | The figure covers care workers in residential care homes for the elderly. | |

| (4) | In England, the children vaccination programme for 2016-2017 was delivered as follows: children aged two to under five years received their vaccination in general practitioners' clinics while children aged five to under eight years received their vaccination in schools. | |

| (5) | The figures cover vaccinations delivered in both the public and private sectors. |

- Added to the above, the experience of England indicates that nasal influenza vaccine has been an effective alternative to traditional injectable vaccine for children and may enhance their acceptance of vaccination. In the US and England, recommendation or reminder delivered by a healthcare professional is proven to be effective in boosting the take-up rate of seasonal influenza vaccination.

Prepared by Ivy CHENG

Research Office

Information Services Division

Legislative Council Secretariat

18 May 2018

Endnotes:

References:

| Hong Kong

| |

| 1. | Centre for Health Protection. (2017) Seasonal Influenza.

|

| 2. | Centre for Health Protection. (2018a) Flu Express.

|

| 3. | Centre for Health Protection. (2018b) Seasonal Influenza Vaccine.

|

| 4. | Food and Health Bureau. (2016) Replies to initial written questions raised by Finance Committee Members in examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2016-17.

|

| 5. | Food and Health Bureau. (2017) Replies to initial written questions raised by Finance Committee Members in examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2017-18.

|

| 6. | Food and Health Bureau. (2018) Replies to initial written questions raised by Finance Committee Members in examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2018-19.

|

| 7. | Food and Health Bureau et al. (2017) Preparation for Winter Surge. LC Paper No. CB(2)296/17-18(04).

|

| 8. | Food and Health Bureau et al. (2018) Response Measures for Seasonal Influenza. LC Paper No. CB(2)1022/17-18(07).

|

| 9. | GovHK. (2018a) Press Releases: LCQ2 – Seasonal influenza vaccination.

|

| 10. | GovHK. (2018b) Press Releases: LCQ22 – Influenza surges.

|

| 11. | Legislative Council Secretariat. (2018) Measures for the prevention and control of seasonal influenza. LC Paper No. CB(2)1022/17-18(08).

|

| Others

| |

| 12. | Bach, A. and Goad, J. (2015) The role of community pharmacy-based vaccination in the USA: current practice and future directions.

|

| 13. | British Journal of General Practice. (2016) Editorials – Influenza vaccination in the UK and across Europe.

|

| 14. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the United States. (2009) Questions & Answers: 2009 H1N1 Nasal Spray Vaccine.

|

| 15. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the United States. (2017a) Estimated Influenza Illnesses, Medical Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths Averted by Vaccination in the United States.

|

| 16. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the United States. (2017b) 2016-17 Influenza Season Vaccination Coverage Dashboard.

|

| 17. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the United States. (2017c) Flu Vaccination Coverage, United States, 2016-17 Influenza Season.

|

| 18. | CNN. (2017) CDC panel again advises against FluMist.

|

| 19. | Dexter, L. J. et al. (undated) Increasing influenza immunisation.

|

| 20. | Gov.UK. (2017) Nasal spray effective at protecting vaccinated children from flu.

|

| 21. | Gov.UK. (2018) Vaccine uptake guidance and the latest coverage data.

|

| 22. | International Pharmaceutical Federation. (2016) An overview of current pharmacy impact on immunization ─ A global report 2016.

|

| 23. | National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. (2012) Improving Childhood Influenza Immunization Rates.

|

| 24. | National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. (2015) Flu Care in Day Care: The Impact of Vaccination Requirements.

|

| 25. | NHS Choices. (2016) Vaccinations ─ Children's flu vaccine.

|

| 26. | Penn State College of Medicine News. (2017) Flu vaccine rates in children may drop when the nasal spray vaccine is unavailable.

|

| 27. | Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. (2018) Flu Vaccination Service.

|

| 28. | Public Health England. (2016) Effectiveness of LAIV in children in the UK.

|

| 29. | Time. (2018) The Nasal Flu Vaccine is Set to Come Back Next Year. Here's What to Know About It.

|

| 30. | WebMD. (2018) Immunizations ─ Flu Shot or Nasal Spray.

|

| 31. | World Health Organization. (2017) Media centre: Up to 650 000 people die of respiratory diseases linked to seasonal flu each year.

|

| 32. | World Health Organization. (2018) Media centre: Influenza (Seasonal) – Fact sheet.

|

| 33. | 衛生福利部疾病管制署:《106年度流感疫苗接種計畫》,2017年。

|

| 34. | 衛生福利部疾病管制署:《流感併發重症》,2018年。

|

Essentials are compiled for Members and Committees of the Legislative Council. They are not legal or other professional advice and shall not be relied on as such. Essentials are subject to copyright owned by The Legislative Council Commission (The Commission). The Commission permits accurate reproduction of Essentials for non-commercial use in a manner not adversely affecting the Legislative Council, provided that acknowledgement is made stating the Research Office of the Legislative Council Secretariat as the source and one copy of the reproduction is sent to the Legislative Council Library. The paper number of this issue of Essentials is ISE06/17-18.