ISE29/20-21

| Subject: | transport, road safety |

- In Hong Kong, babies and toddlers aged below three travelling in the front seats of private cars are mandatorily required to use protective child car seats ("CCSs"), alternatively called "child restraint devices", under the Road Traffic (Safety Equipment) Regulations (Cap. 374F) ("the Regulations"). Yet older children aged at least three are not required to do so, nor children in the rear seats. As there were 162 injuries for child passengers aged under 12 in private cars each year during the past decade, coupled with study findings that CCSs could reduce child injuries by up to 80%, there are calls to tighten the statutory seating requirements for children.1Legend symbol denoting World Health Organization (2009 and 2018) and data from Transport Department.

- In December 2013, the Government proposed extending the statutory CCS requirement (a) to older children up to age 10 and (b) from front seats to rear seats of private cars. While the suggestion was supported by Members of the Legislative Council ("LegCo") and the Consumer Council, the progress of the proposed legislative amendment is slow, partly due to "complicated issues" in enforcement (e.g. penalties and collection of evidence).2Legend symbol denoting Consumer Council (2019) and GovHK (2018 and 2021). Most recently in June 2021, the Government indicated that it was still balancing "the views of various parties" and would consult the LegCo again once further details are formulated.

- Globally, more than 40 places have enacted tighter laws on CCS usage in private cars. More specifically in the United Kingdom ("UK"), its CCS law is widely acclaimed as a good practice, in the light of its comprehensiveness and high CCS usage rate hitting 95%.3Legend symbol denoting World Health Organization (2018). This issue of Essentials gives a concise account of salient features of the regulatory regime of CCSs in the UK, after a quick review of global trends and respective policy developments in Hong Kong.

Justifications and global trends for usage of child car seats

- Risks of applying adult seat belts to children: With their smaller body size, shorter height and weaker muscles, children wearing adult seat belts could face additional injury risks in the event of sudden braking or collision. Taking the conventional diagonal adult seat belts as an example, they could cause abdominal injuries among children (because the skeleton of a child is less developed to protect the abdomen) on the one hand, and are not optimally effective to prevent children from ejection in collision (because adult seat belts are considered oversized for their bodies).

- Benefits of CCSs for child safety: Seats tailor-made for children can reduce such risks and offer additional protection to child passengers. Based on a recent report of the World Health Organization ("WHO"), CCSs can reduce children deaths in traffic accidents by as much as 60%. For injury prevention, CCSs can reduce the injury risk of children under five by 80% and older children aged 5-9 by 52%.4Legend symbol denoting By comparison, adult seat belts can only reduce the risk of injury by 32% for children under five and 19% for those aged 5-9. See World Health Organization (2009 and 2018)..

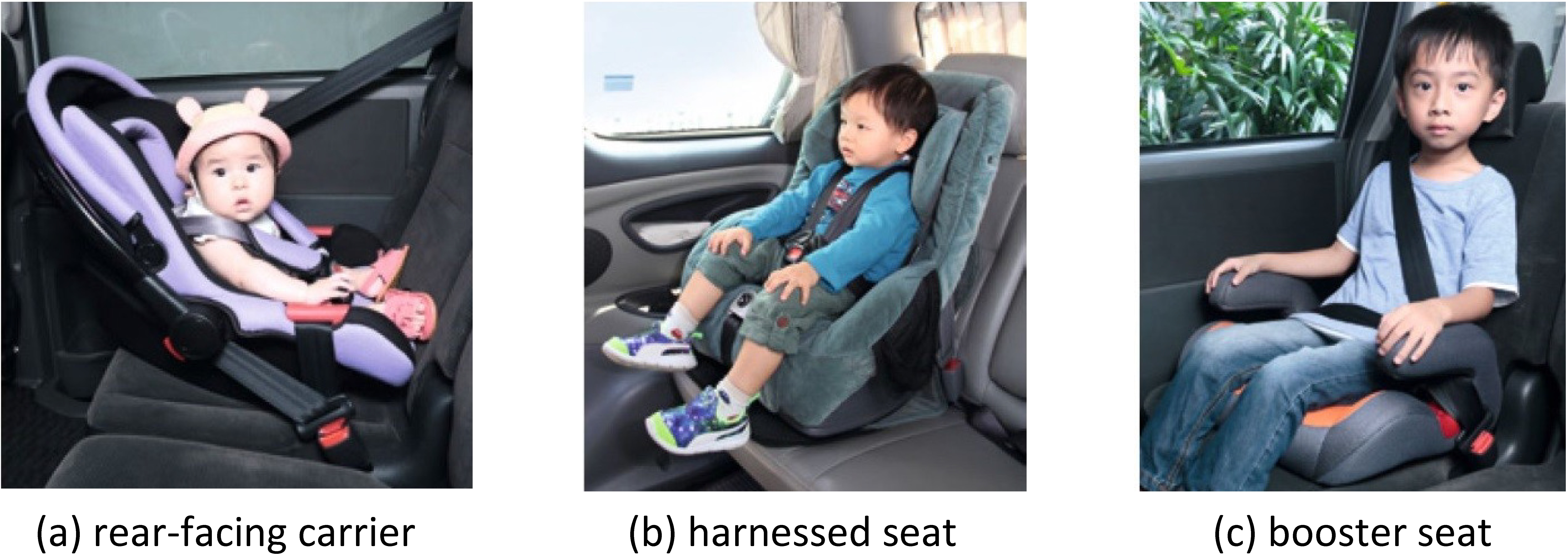

- Global safety standards of CCSs: In line with safety recommendations of the United Nations ("UN"), rear-facing carriers are recommended for babies or toddlers under 9 kg or 15 months old.5Legend symbol denoting There are two sets of UN safety standards, namely R44/04 and the more stringent R129, which was introduced in 2013 and will gradually replace R44/04. Both prescribe requirements on testing and usage. See United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (2015). Harnessed seats (with built-in straps) or booster seats (helping children better fit into adult seat belts) are recommended for older children, with variations in specifications based on their weight or height (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Three major types of child car seats

Source: Transport Department.

- Global effectiveness of CCSs: According to the WHO study in 2018, 41 places (23%) in the world have already enacted tighter laws mandating CCS usage for children less than 10 years old or less than 135 cm when travelling in private cars.6Legend symbol denoting World Health Organization (2018). They include many advanced places such as the UK, Singapore and all 27 member states of the EU.

Legislation in advanced places appears to have contributed to high usage rates of CCSs by 2017, including 91% in Canada, 95% in the UK and over 90% in many member states of EU.7Legend symbol denoting While legislation is "essential", WHO stated that success in these places was also attributable to education and enforcement. See World Health Organization (2009 and 2018). High usage rates in turn led to reduction of child deaths in road accidents, as manifested in a decrease of such deaths in the EU by an average of 7.3% annually during 2006-2016.8Legend symbol denoting European Transport Safety Council (2018).

Recent policy developments on child car seats in Hong Kong

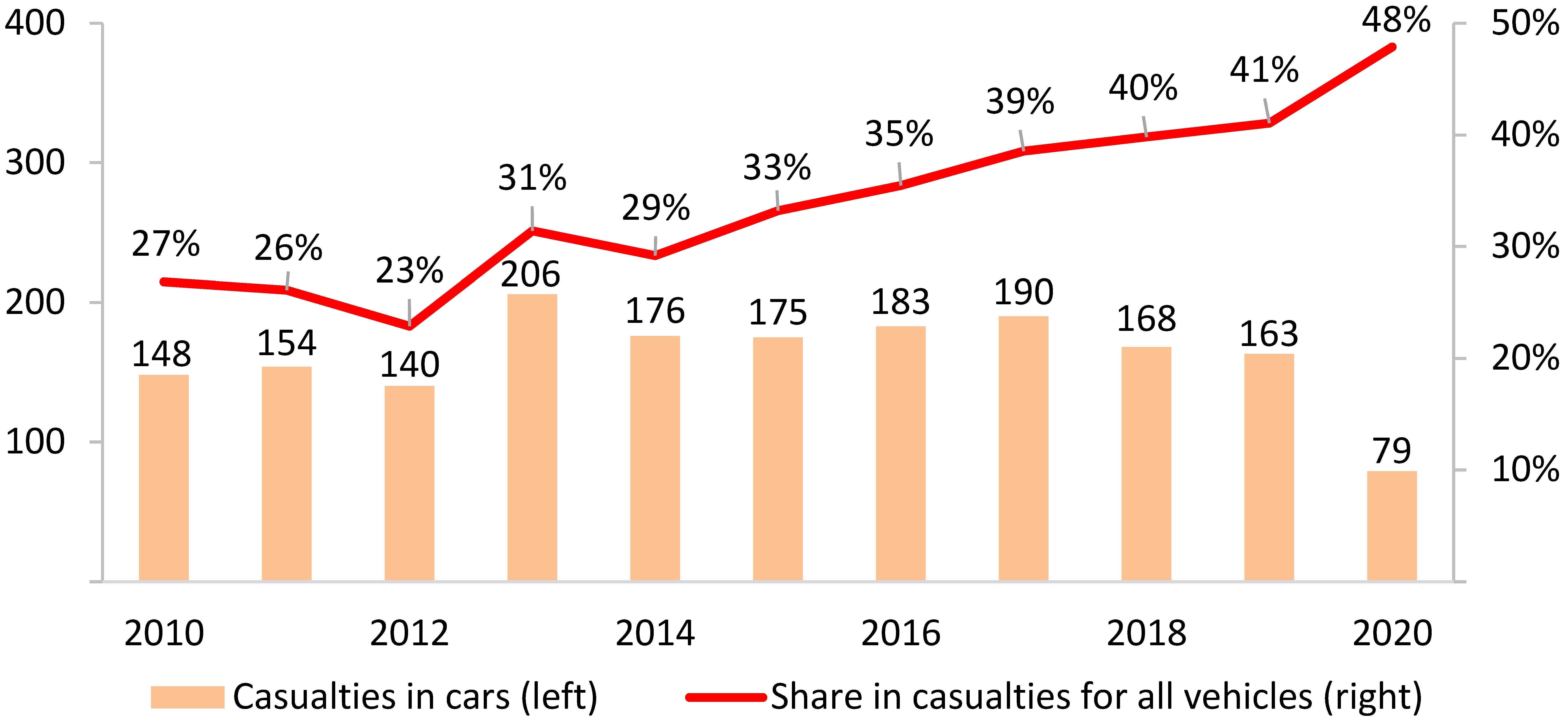

- Child passenger injuries in private cars: Private cars have consistently been the largest source of child passenger injuries over the past decade (with a share of 32%), way above school buses (21%), public buses (21%) and taxis (12%). The number of child passengers aged below 12 in private cars suffering injuries in traffic accidents averaged at 162 annually over the past decade, in spite of a noticeable drop amidst the pandemic in 2020 (Figure 2). Fortunately, no child fatality has been recorded for seven consecutive years since 2014, after two deaths in 2013.

Figure 2 - Casualties of child passengers aged under 12 in private cars

Source: Transport Department.

- Existing legislation for CCSs: After the revision of the Regulations in 1996, use of CCSs in private cars is mandatory for (a) children aged under three when travelling in front seats; and (b) children in rear seats if CCSs are available. In other words, CCSs are still not mandatory for children in rear seats, nor for children aged three and above.

- Proposed tightening after regulatory review in 2013: After a review of the respective CCS legislation in 17 places (including Japan, Australia, the UK and Canada) in early 2010s, the Government noted that their statutory requirements were all more stringent than those in Hong Kong. With a view to aligning with the good practice in the advanced places, the Government intended to extend the statutory requirements to children aged at least three and to rear seats.

In a proposal submitted to the LegCo Panel on Transport ("the Panel") in December 2013, the Government said that it was prudent to use both body height and age as the criteria in mandating usage of CCSs in private cars. Taking also into account the advice of the local medical community, it put forward four age-height options, with children below both thresholds subject to proposed regulation. In the ascending order of stringency of requirements, these options are (a) 135 cm or 8-year-old; (b) 140 cm or 9-year-old; (c) 145 cm or 10-year-old; and (d) 150 cm or 11-year-old.9Legend symbol denoting Transport and Housing Bureau (2013). - Issues of concern: While Members of the Panel generally supported the proposal in 2013, they did not indicate specific preference amongst the four age-height options. The Government and some LegCo Members also raised a few concerns:

(a) a tightening in statutory requirement would have cost impacts on car-owning families with younger children: based on the Travel Characteristics Survey 2011, there were 75 000-99 000 such families, and the cost of buying CCSs was estimated to be HK$4,000-HK$14,200 per child; (b) non-car-owning families would be affected as well, as their younger children could not travel in private cars of their friends/relatives on an ad hoc basis; and (c) while the Police would need to measure children's height in enforcement, there would also be "complicated issues" relating to "the penalty levels, the collection of evidence, the circumstances for motorists to establish a reasonable defence and other enforcement details".10Legend symbol denoting Legislative Council Secretariat (2013) and GovHK (2018 and 2021). - Recent policy stance in mid-2021: Although the Government indicated that it would draft the legislation in 2014 after consulting relevant parties and conducting a survey on the opinion of private car owners, little visible progress has been made over the past eight years.11Legend symbol denoting Legislation Council Secretariat (2013). In reply to two questions raised at the LegCo in May 2018 and June 2021 respectively, the Government reiterated that there was "room to further strengthen the protection for child passengers", but it still needed to "balance the views of various parties". It pledged to consult the Panel and the stakeholders again upon "further formulation of details".12Legend symbol denoting GovHK (2018 and 2021).

Mandatory requirements of child car seats in the United Kingdom

- Two decades ago, the UK still confined the mandatory requirement for CCSs only to children aged under three riding in the front seats, i.e. similar to the existing practice in Hong Kong. The wind for change began in 2003, when the EU passed a binding directive on mandatory CCS usage for children with height below 135 cm in all member states (though without any age threshold). In a follow-up survey conducted in 2004, three-fifths (63%) of the UK parents indicated that they stopped using CCSs before their children turned six, precipitating legislative amendment.13Legend symbol denoting BBC (2004).

- The Motor Vehicles (Wearing of Seat Belts) (Amendment) Regulations was subsequently passed in the UK in 2006, extending the mandatory CCS requirement to older children and to those riding in the rear seats. This was followed by a further amendment in 2015 to incorporate updated safety standards of CCSs as recommended by the UN. Here are the salient features of the regulatory regime in the UK:14Legend symbol denoting Department for Transport (2006 and 2015a).

(a) Age and height thresholds: Children travelling in private cars must use CCSs before reaching 135 cm or the age of 12, whichever comes first. While the height threshold follows the EU directive, the age threshold is entirely set by the UK government. It is considered that teenagers reaching the age of 12 are safe enough to use adult seat belts, as marginal safety benefits brought by a CCS become very modest;15Legend symbol denoting House of Commons (2006). (b) No air bags for rear-facing CCSs in front seats: While children travel in rear-facing CCSs in front seats of private cars, the air-bag must be deactivated to avoid potential serious injuries in case of collision; (c) Penalties: The driver will be subject to a fine of £100-£500 (HK$1,074-HK$5,370) for each count of failure to use an appropriate CCS. The fine is set at the same level as the penalty for adults not wearing seat belts; (d) Special exemptions addressing practical concerns of drivers: The law allows a child to travel without a CCS (i) if there are medical reasons; (ii) in a taxi or private hire car without CCSs; (iii) in a car without CCSs for a short distance and with unexpected necessity; or (iv) when there is no room for a third CCS. However, conditions (iii) and (iv) apply only to children aged three and above; and (e) Safety standards of CCSs: In line with the practice in the EU, CCSs in the UK need to comply with product safety standards specified by the UN.16Legend symbol denoting Meanwhile, some other places (e.g. Australia and Canada) would choose to set their own safety standards. - Enforcement concerns: While the proposed mandatory requirement of CCS was generally accepted by the UK community in the mid-2000s, there were concerns over (a) difficulties of enforcement in checking the age and height of child passengers in moving cars; and (b) whether parents could understand the new requirements. The police in the UK acknowledged such challenges. Apart from pledging to enforce the law in "their normal judicious and intelligent way", the UK police also put additional efforts into making occasional presence at school areas to remind parents of the relevant requirements,17Legend symbol denoting BBC (2006), House of Commons (2006) and House of Lords (2006). offering free CSS checks at car parks to ensure their safe installation, and conducting high-profile safety campaigns.18Legend symbol denoting Such checks are intended to be educational, so drivers are allowed to correct mistakes immediately instead of being imposed with fines. See South Gloucestershire Council (2014) and Child Seat Safety (2021).

- Policy effectiveness: In 2017, the usage rate of CSSs in the UK was 95%, which was considered high by global standard. Annually, some 4 600 offences related to violation of CCS rules were recorded by the police on average during 2015-2017.19Legend symbol denoting World Health Organization (2018), The Mirror (2017) and Confused.com (2018). The law, combined with the various education and awareness initiatives, appears to have positive impact on the safety of child passengers, with the number of children under 12 killed or seriously injured when travelling in cars halving from 515 in 2002 to 235 in 2020.20Legend symbol denoting BBC (2004) and Department for Transport (2021). A government report published in 2015 indeed pinpointed that such a sharp decrease was attributable to the use of CCSs, though it acknowledged that other factors such as better designs of roads and vehicles contributed to the good performance as well.21Legend symbol denoting Department for Transport (2015b).

Prepared by Germaine LAU

Research Office

Information Services Division

Legislative Council Secretariat

7 October 2021

Endnotes:

References:

| Hong Kong

| |

| 1. | Consumer Council. (2019) Weak Protection in 4 Models of Child Car Seats Room for Improvement in Safety Design.

|

| 2. | GovHK. (2018) LCQ3: Child Restraint Device.

|

| 3. | GovHK. (2021) LCQ6: Child Safety in Cars.

|

| 4. | Legislation Council Secretariat. (2013) Minutes of Meeting of Panel on Transport, 20 December. LC Paper No. CB(1)920/13-14.

|

| 5. | Legislation Council Secretariat. (2019) Measures to Contain Private Car Growth in Selected Places. LC Paper No. IN21/18-19.

|

| 6. | Transport Department. (2021) Child Safety in Cars.

|

| 7. | Transport and Housing Bureau. (2013) Proposal to Raise the Mandatory Requirement of Using Child Restraint Device in Private Cars. LC Paper No. CB(1)543/13-14(05).

|

| The United Kingdom

| |

| 8. | BBC. (2004) Use Car Seats up to Age of 11. 15 April.

|

| 9. | BBC. (2006) New Child Car Seat Laws in Force. 18 September.

|

| 10. | Child Seat Safety. (2021) Upcoming Events 2021.

|

| 11. | Confused.com. (2018) Parents Still Baffled by Car Seat Laws.

|

| 12. | Department for Transport. (2006) Explanatory Memorandum to the Motor Vehicles (Wearing of Seat Belts) (Amendment) Regulations 2006.

|

| 13. | Department for Transport. (2015a) Explanatory Memorandum to the Motor Vehicles (Wearing of Seat Belts by Children in Front Seats) (Amendment) Regulations 2015.

|

| 14. | Department for Transport. (2015b) Facts on Child Casualties. June 2015.

|

| 15. | Department for Transport. (2021) Reported Casualties by Age Band, Road User Type and Severity, Great Britain, 2020.

|

| 16. | House of Commons. (2006) Delegated Legislation Standing Committee Debates - Draft Motor Vehicles (Wearing of Seat Belts) (Amendment) Regulations 2006. 5 July.

|

| 17. | House of Lords. (2006) Debates on Motor Vehicles (Wearing of Seat Belts) (Amendment) Regulations 2006. 12 July.

|

| 18. | South Gloucestershire Council. (2014) Police and Council Offer Child Car Seat Safety Checks.

|

| 19. | The Mirror. (2017) Child Car Seat Regulations Changed on March 1. 19 May.

|

| Others

| |

| 20. | European Transport Safety Council. (2018) Reducing Child Deaths on European Roads.

|

| 21. | United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. (2015) UN Regulation No 129: Increasing the Safety of Children in Vehicles for Policymakers and Concerned Citizens.

|

| 22. | World Health Organization. (2009) Seat-Belts and Child Restraints: A Road Safety Manual for Decision-Makers and Practitioners.

|

| 23. | World Health Organization. (2018) Global Status Report on Road Safety 2018.

|

Essentials are compiled for Members and Committees of the Legislative Council. They are not legal or other professional advice and shall not be relied on as such. Essentials are subject to copyright owned by The Legislative Council Commission (The Commission). The Commission permits accurate reproduction of Essentials for non-commercial use in a manner not adversely affecting the Legislative Council. Please refer to the Disclaimer and Copyright Notice on the Legislative Council website at www.legco.gov.hk for details. The paper number of this issue of Essentials is ISE29/20-21.